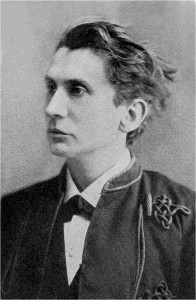

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

Venus in Furs

Leopold von Sacher Masoch – gave the name to Masochism.

Masochism is the tendency to derive pleasure, especially sexual pleasure, from one’s own pain or humiliation, and its named after Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1839-95) the Austrian writer who described it so well in his novels. “Venus in Furs” is probably his best known work, a romantic tale which has at its heart a sado/masochistic relationship. From this work the term ‘masochism’ was coined, and Leopold received the ultimate accolade of having a whole perversion named after him. How cool !

His writing – The novel ‘Venus in Furs’ was part of an epic series he planned called “The Heritage of Cain,” which was to have had six parts, each made up of several stories: the six parts were to be Love, Property, The State, War, Work, and Death. “Venus in Furs” was part of Love, which contained five additional stories and was first published in 1870.The novel drew heavily on Sacher-Masoch’s own life. The real-life model for the book’s main female character, Wanda, was a woman named Fanny Pistor. This lady first contacted Sacher-Masoch, then emerging as a new literary talent, for suggestions on her own chances for publication but an intense relationship quickly followed.On December 8, 1869 Leopold and Fanny signed a contract making Leopold von Sacher-Masoch the slave of Fanny Pistor for a period of six months, with the stipulation, doubtlessly at Sacher-Masoch’s suggestion, that the Baroness wear furs as often as possible, especially when she was in a ‘cruel’ mood. Sacher-Masoch was given the alias of “Gregor,” and disguised as the servant of Fanny. The two traveled by train to Italy, living their mistress/slave roles. As with the character in his novel, Sacher-Masoch traveled in the third class compartment while his ‘mistress’ had a seat in first class, arriving in Venice (Florence, in the novel), where they were not known and would not arouse suspicion. ‘Venus in Furs’ takes threads from Sacher-Masoch’s own life and weaves them into a dark sexual myth.

The making of a masochist – as a child Leopold was greatly attracted by representations of cruelty; he loved to gaze at pictures of executions, the legends of martyrs were his favorite reading, and with the onset of puberty he regularly dreamed that he was fettered and in the power of a cruel woman who tortured him. It has been said by an anonymous author that the women of Galicia either rule their husbands entirely and make them their slaves or themselves sink to be the wretchedest of slaves. At the age of 10, according to Schlichtegroll’s narrative, the child Leopold witnessed a scene in which a woman of the former kind, a certain Countess Xenobia X., a relative of his own on the paternal side, played the chief part, and this scene left an undying impress on his imagination. The Countess was a beautiful but wanton creature, the child adored her, impressed alike by her beauty and the costly furs she wore. She accepted his devotion and little services and with sometimes allow him to assist her in dressing; on one occasion, as he was kneeling before her to put on her ermine slippers, he kissed her feet; she smiled and gave him a kick which filled him with pleasure. Not long afterward occurred the episode which so profoundly affected his imagination. He was playing with his sisters at hide-and-seek and had carefully hidden himself behind the dresses on a clothes-rail in the Countess’s bedroom. At this moment the Countess suddenly entered the house and ascended the stairs, followed by a lover, and the child, who dared not betray his presence, saw the Countess sink down on a sofa and begin to caress her lover. But a few moments later the husband, accompanied by two friends, dashed into the room.

Before, however, he could decide which of the lovers to turn against the Countess had risen and struck him so powerful a blow in the face with her fist that he fell back streaming with blood. She then seized a whip, drove all three men out of the room, and in the confusion the lover slipped away. At this moment the clothes-rail fell and the child, the involuntary witness of the scene, was revealed to the Countess, who now fell on him in anger, threw him to the ground, pressed her knee on his shoulder, and struck him unmercifully. The pain was great, and yet he was conscious of a strange pleasure. While this castigation was proceeding the Count returned, no longer in a rage, but meek and humble as a slave, and kneeled down before her to beg forgiveness. As the boy escaped he saw her kick her husband. The child could not resist the temptation to return to the spot; the door was closed and he could see nothing, but he heard the sound of the whip and the groans it produced.

“I should like to see her in furs” – if any of this is even remotely true, then its easy to understand the origins of the emotional attitude which affected so much of Sacher-Masoch’s work. As his biographer remarks, woman became to him, during a considerable part of his life, a creature at once to be loved and hated, a being whose beauty and brutality enabled her to set foot at will on the necks of men, and in the heroine of his first important novel, the Emissär, dealing with the Polish Revolution, he embodied the contradictory personality of Countess Xenobia. Even the whip and the fur garments, Sacher-Masoch’s favorite emotional symbols, find their explanation in this early episode. He was accustomed to say of an attractive woman: and, of an unattractive woman: “I could not imagine her in furs.” His writing-paper at one time was adorned with a figure in Russian Boyar costume, her cloak lined with ermine, and brandishing a scourge. On his walls he liked pictures of women in furs, of the kind of which there is so magnificent an example by Rubens in the gallery at Munich. He would even keep a woman’s fur cloak on an ottoman in his study and stroke it from time to time, finding that his brain thus received the same kind of stimulation as Schiller found in the odor of rotten apples.

Becoming a writer – at the Universities of Prague and Graz he studied with such zeal that when only 19 he took his doctor’s degree in law and shortly afterward became a privatdocent for German history at Graz. Gradually, however, the charms of literature asserted themselves definitively, and he soon abandoned teaching. He took part, however, in the war of 1866 in Italy, and the battle of Solferino he was decorated on the field for bravery in action by the Austrian field-marshal. These incidents, however, had little disturbing influence on Sacher-Masoch’s literary career, and he was gradually acquiring a European reputation by his novels and stories.

Wooing Wanda and whips with nails – A far more seriously disturbing influence had already begun to be exerted on his life by a series of love-episodes. Some of these were of slight and ephemeral character; some were a source of unalloyed happiness, all the more so if there was an element of extravagance to appeal to his Quixotic nature. He always longed to give a dramatic and romantic character to his life, his wife says, and he spent some blissful days on an occasion when he ran away to Florence with a Russian princess as her private secretary. Most often these episodes culminated in deception and misery. It was after a relationship of this kind from which he could not free himself for four years that he wrote Die Geschiedene Frau, Passionsgeschichte eines Idealisten, putting into it much of his own personal history. At one time his was engaged to a sweet and charming young girl. Then it was that he met a young woman at Graz, Laura Rümelin, 27 years of age, engaged as a glovemaker, and living with her mother. Though of poor parentage, with little or on knowledge of the world, she had great natural ability and intelligence. Schlichtegroll represents her as spontaneously engaging is a mysterious intrigue with the novelist. Her own detailed narrative renders the circumstances more intelligible. She approached Sacher-Masoch by letter, adopting for disguise the name of his heroine Wanda von Dunajew, in order to recover possession of some compromising letters which had been written to him as a joke, by a friend of hers. Sacher-Masoch insisted on seeing his correspondent before returning the letters, and with his eager thirst for romantic adventure he imagined that she was a married woman of the aristocratic world, probably a Russian countess, whose simple costume was a disguise.

Not anxious to reveal the prosaic facts, she humored him in his imaginations and a web of mysticification was thus formed. A strong attraction grew up on both sides and, though for some time Laura Rümelin maintained the mystery and held herself aloof from him, a relationship formed and a child was born. Thereupon, in 1893, they married. Before long, however, there was disillusion on both sides. She began to detect the morbid, chimerical, and unpractical aspects of his character, and he realized that not only was his wife not an aristocrat, but, what was of more importance to him, she was by no means the domineering heroine of his dreams. Soon after marriage, in the course of an innocent romp in which the whole of the small household took part, he asked his wife to inflict a whipping on him. She refused, and he thereupon suggested that the servant should do it; the wife failed to take this idea seriously; but he had it carried out, with great satisfaction at the severity of the castigation he received. When, however, his wife explained to him that, after this incident, it was impossible for the servant to stay, Sacher-Masoch quite agreed and she was at once discharged. But he constantly found pleasure in placing his wife in awkward or compromising circumstances, a pleasure she was too normal to share. This necessarily led to much domestic wretchedness. He had persuaded her, against her wish, to whip him nearly every day, with whips he devised, having nails attached to them.

“Simple as a child, naughty as a monkey” – He found this a stimulant to his literary work, and it enabled him to dispense in his novels with his stereotyped heroine who is always engaged in subjugating men, for, as he explained to his wife, when he had the reality in his life he was no longer obsessed by it in his imaginative dreams. Not content with this, however, he was constantly desirous for his wife to be unfaithful. He even put an advertisement in a newspaper to the effect that a young an beautiful woman desired to make the acquaintance of an energetic man. The wife, however, though she wished to please her husband, was not anxious to do so to this extent. She went to an hotel by appointment to meet a stranger who answered this advertisement, but when she had explained to him the state of affairs he chivalrously conducted her home. It was some time before Sacher-Masoch eventually succeeded in rendering his wife unfaithful. He attended to the minutest details of her toilette on this occasion, and as he bade her farewell at the door he exclaimed: “How I envy him!” This episode thoroughly humiliated the wife, and from that moment her love for her husband turned to hate. A final separation was only a question of time. Sacher-Masoch formed a relationship with Hulda Meister, who had come to act as secretary and translator to him, while his wife became attached to Rosenthal, a clever journalist later known to readers of the Figaro as “Jacques St.-Cère,” who realized her painful position and felt sympathy and affection for her. She went to live with him in Paris and, having refused to divorce her husband, he eventually obtained a divorce from her; she states, however, that she never at any time had physical relationships with Rosenthal, who was a man or fragile organization and health. Sacher-Masoch united himself to Hulda Meister, who is described by the first wife as a prim and faded but coquettish old maid, and by the biographer as a highly accomplished and gentle woman, who cared for him with almost maternal devotion. No doubt there is truth in both descriptions.

It must be noted that, as Wanda clearly shows, apart from his abnormal sexual temperament, Sacher-Masoch was kind and sympathetic, and he was strongly attached to his eldest child. Eulenburg also quotes the statement of a distinguished Austrian woman writer with him that, “apart from his sexual eccentricities, he was an amiable, simple, and sympathetic man with a touchingly tender love for his children.” He had very few needs, did not drink nor smoke, and though he liked to put the woman he was attached to in rich furs and fantastically gorgeous raiment he dressed himself with extreme simplicity. His wife quotes the saying of another woman that he was as simple as child and as naughty as a monkey.

Later life – in 1883 Sacher-Masoch and Hulda Meister settled in Lindheim, a village in Germany near the Taunus, a spot to which the novelist seems to have been attached because in the ground of his little estate was a haunted and ruined tower associated with a tragic medieval episode. Here, after many legal delays, Sacher-Masoch was able to render his union with Hulda Meister legitimate; here two children were in due course born, and here the novelist spent the remaining years of his life in comparative peace. At first, as is usual, treated with suspicion by the peasants, Sacher-Masoch gradually acquired great influence over them; he became a kind of Tolstoy in the rural life around him, the friend and confidant of all the villagers (something of Tolsoy’s communism is also, it appears, to be seen in the books he wrote at this time), while the theatrical performances which he inaugurated, and in which his wife took an active part, spread the fame of the household in many neighboring villages. Sadly his health began to break down and he died on March 9, 1895.